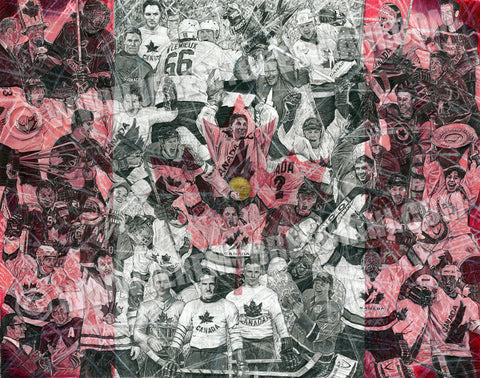

“Canada's Game"

Click to READ CUSTOMER REVIEWS

GUARANTEED DELIVERY BEFORE CHRISTMAS!!

on all orders placed by December 20

GUARANTEED DELIVERY BEFORE CHRISTMAS!!

on all orders placed by December 20

Canada's Game. This drawing took 517 hours to complete. The original and Limited Edition prints are now available for purchase on my website. I drew this artwork live at 37 different events from January through October this year.

My goal was to capture the greatest moments in Team Canada hockey history. I started with the big five: The 1972 Canada v. Russia Summit Series, the 1976 Canada Cup, the 1987 Canada Cup, the 2002 Double Gold Olympics and the 2010 Golden Goal. I then researched all major championships throughout Canadian hockey history (from 1910 on) and tried to incorporate players and moments that best captured those moments. The placement of the Lucky Loonie under the center ice dot in the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics was special to me and that led to my decision to encapsulate all of these incredible moments under a sheet of ice. Once the piece was complete in black and white, I went over it with various shades of red coloured pencils to create a transparent Canadian flag.

Each of these players/moments is important in Canadian hockey history and deserves its own description/story, so I have done just that below.

1. 2010 Olympics (The Golden Goal. Feb. 28, 2010).

With a home-ice gold medal on the line in overtime at the Vancouver Olympics and an unprecedented number of Canadians tuned in, Sidney Crosby took a pass from Jarome Iginla and quickly slid the puck past a surprised Ryan Miller, sending the entire nation into instant party mode. While it may not have been a Picasso in terms of artistry, it made for great drama due to the sheer pressure of the situation.

Scott Niedermayer is also drawn in this artwork as he is the only Canadian, as of 2010, to have won the Stanley Cup, the Memorial Cup, the World Junior Championships (1991), the World Championships (2004), the World Cup of Hockey (2004), and the Winter Olympics (2002 and 2010).

2. 1972 Summit Series (Henderson Scores For Canada. Sept. 28, 1972).

The Summit Series was cloaked in Cold War intrigue, a political land mine that had a nation on tenterhooks. After falling behind early to the Soviets, Canada clawed its way back in the eight-game showdown and Paul Henderson’s third consecutive game-winner sealed the comeback. And once again, Canada could breathe.

Played during the Cold War, the series was viewed as a battle for both hockey and cultural supremacy. Paul Henderson scored the game-winning goal in the sixth, seventh and eighth games, the last of which has become legendary in Canada and made him a national hero. It was voted the "sports moment of the century" by The Canadian Press and earned him numerous accolades. Henderson has twice been inducted into Canada's Sports Hall of Fame: in 1995 individually and in 2005 along with all players of the Summit Series team. He was inducted into the International Ice Hockey Federation Hall of Fame in 2013.

In his memoir, The Goal of My Life, Henderson describes Game Eight’s indelible moment.

Time ticked down. There was less than a minute to play at Luzhniki Arena in Moscow and the fans, including the 3,000 Canadians present, were on the edge of their seats. Phil Esposito, Yvan Cournoyer, and Peter Mahovlich were on the ice in that final minute as I watched from the bench. I then did something I had never done before, and would never do again in my hockey career.

“Pete! Pete!” I hollered at him. Don’t ask me how or why, but I felt if I could get out there one more time I could score a goal. I just felt it. For the first time in my life I was screaming at a player to get off the ice so I could get on, just one more time. You just didn’t do that—I had never heard another player do it in my 18-year hockey career—but I did.

“Pete! Pete!” I hollered for a second time and then a third. Finally, Mahovlich skated over to the bench, allowing me to hop over the boards and join the play.

As I got onto the ice, the puck went to Cournoyer on the far boards. I charged to the net and yelled for a pass, but when it came I had to reach forward for it and their defenceman tripped me, my momentum making me fall and slide into the boards behind the Russian goal.

I remember thinking that I still had time to get the puck back again and score. The Russians tried to clear the zone, but Esposito was able to whack the puck toward Soviet goaltender Vladislav Tretiak, who made the save. I was on my feet again and alone at the side of the goal, and when Tretiak couldn’t control the rebound off Esposito’s shot, I tried sliding a shot along the ice, but he blocked it.

The puck came right back to me. With Tretiak now down, I had some room, and I put the puck in the back of the net, with 34 seconds left on the clock. And then . . . well, perhaps the best way to describe the whole few moments was the way Foster Hewitt did to millions of Canadians watching at home on television.

“Here’s a shot! Henderson made a wild stab at it and fell. Here’s another shot, right in front. They score! Henderson has scored for Canada!”

I have been asked a million times what went through my mind when that puck slid into the goal. I have answered it a million times, but I will tell you one more time now what I even said to myself out loud when that puck went in the net.

“Dad would have loved that one,” I said. I even had a sense of melancholy for a nanosecond that he wasn’t there to share the moment with me, as he had died in 1968. He was the most influential person in my life when it came to hockey, and at the greatest moment of my hockey life, I wanted to share it with him. After all those years, I guess I was still trying to please my father.

That moment of sadness lasted just a second, though, and was replaced by absolute jubilation! I jumped into Cournoyer’s arms, the guys came pouring off the bench, and the celebration was on. My goodness, what a moment in time that was; I still get tingles thinking about it 40 years later.

Another moment, I had to capture in this artwork was the Phil Esposito interview ("The Speech") Following a loss to the Soviets in game four, Phil Esposito's famous speech in a TV interview inspired the team and rallied the Canadian fans. "We're disillusioned and disappointed. We cannot believe the bad press we've got, the booing we've got in our own building," said Espo, "I'm completely disappointed. I cannot believe it. Every one of us guys... we came because we love our country. Not for any other reason. We came because we love Canada."

3. 1987 Canada Cup (Lemieux from Gretzky. Sept. 15, 1987).

One of the last major Soviet-Canada tilts, the teams met again in the Canada Cup final. With the series tied at one game apiece, Mario Lemieux took a feed on the rush from Wayne Gretzky and roofed the winner. It was the game’s two greatest talents, maybe of all-time, clicking to create a once-in-a-lifetime moment.

4. 1976 Canada Cup (Sittler in Overtime. Sept. 15, 1976).

In the decisive second game of the best-of-three Canada Cup, Darryl Sittler streaked down the left side of the ice in overtime and drew Czechoslovakian goaltender Vladimir Dzurilla far out of the crease with a fake shot. The Maple Leafs captain then slid the puck into an open net and helped cement his Hall-of-Fame legacy.

5. 2002 Olympics (DOUBLE GOLD!)

The 2002 Olympics were a sequel, of sorts, for hockey — and no country carried more baggage into the Games than Canada. Four years earlier, women’s hockey made its Olympic debut in Japan, where the Canadians — the world’s leading team — were upset by the United States in the gold medal game. Meanwhile, on the men’s side, Canada’s entry at the first Games to feature NHLers met its demise in a gut-wrenching semifinal shootout loss to Dominik Hasek and the Czech Republic. What’s more, the Canadian men had not won Olympic gold in the sport its country invented since 1952, marking a 50-year drought when they headed to Salt Lake City.

2002 was a second chance for Canada to win its first Olympic gold in Women's Ice Hockey, and Hailey Wickenheiser was named to Canada's roster for the Winter Olympics held in Salt Lake City, Utah. On Team Canada's pre-Olympic tour, Wickenheiser played 26 games and racked up 36 points.

Facing USA in the final, with just over four minutes left on the clock, Canada was called for one final infraction — the 13th penalty called on them, compared to six against Team USA. Karyn Bye cashed in on a power-play goal to make it 3–2. In the final minutes, the Americans pulled DeCosta, but even facing six attackers, the Canadians — with the men’s team in attendance and cheering wildly — hung on to win gold. It was a nice bit of redemption for 1998. Wickenheiser was named Tournament MVP and she was the top scorer on the Women's side.

Wickenheiser was a member of the Canadian women's national ice hockey team for 23 years (from 1994 until announcing her retirement on January 13, 2017) and is the team's career points leader with 168 goals and 211 assists in 276 games. She represented Canada at the Winter Olympics five times, capturing four gold and one silver medal and twice being named tournament MVP, and is a seven-time winner of the world championships. She is tied with teammates Caroline Ouellette and Jayna Hefford for the record for the most gold medals of any Canadian Olympian, and is widely considered to be the greatest female ice hockey player of all time. On February 20, 2014, Wickenheiser was elected to the International Olympic Committee's Athletes' Commission. In 2019, she was named to the Hockey Hall of Fame, in her first year of eligibility. She was also inducted into the IIHF Hall of Fame in 2019.

Three days after Canada’s women won gold, the Canadian men squared off against the United States in the men’s final. The last time these two teams met in a best-on-best final, the Americans had won a best-of-three series in the 1996 World Cup — on Canadian soil, no less — to puncture Canada’s long run of dominance in those events. Mike Richter, the American goalie who’d stonewalled the Canadians in ’96, was once again staring down the Red-and-White. With six years of recent heartache and a half-century long Olympic gold drought in tow, Canada hit the ice.

Brodeur did his part, and a pair of Canadian linemates put together performances in “game of his life” territory. First, Iginla potted his second of the day, providing some breathing room with 3:59 to play. Then came the dagger: With 80 seconds remaining, Sakic got his second, swooping in alone on Richter and releasing his classic wrister to the blocker side, bulging the twine and sending everyone associated with Team Canada into a state of delirium. In the stands, Gretzky raised two fists and pumped them like he was punching a hole in the roof. From Newfoundland to B.C., Canadians belted out screams, matching the excitement of play-by-play man Bob Cole. “Bob Cole took the name ‘Joe’ and made it into three syllables. ‘Gee-ooo-ooh Sakic! That makes it 5–2 Canada! Surely that’s going to be it!’”

6. 1910. (The Oxford Canadians)

The Oxford Canadians were an English amateur ice hockey team, originally formed from Rhodes Scholars who were attending Oxford University. They were the first ice hockey team representing Canada to wear a red maple leaf on their uniform. They were English Champions in 1907 and won the European Championship in 1910. The club became affiliated to the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1911. They were named English champions again in 1911, and participated in the 1912 LIHG Championship, which were unofficially considered to be "World Championships". The Oxford Canadians were the only "non-European" participants in the tournament, in which they finished second behind Berliner Schlittschuhclub, who were representing Germany in the competition. The club were the English champions for the fourth and final time in 1913. Ice hockey was suspended in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

7. 1920 Summer Olympics (Winnipeg Falcons)

The Winnipeg Falcons were a senior men's amateur ice hockey team based in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Winnipeg Falcons won the 1920 Allan Cup. That team went on to represent Canada in the 1920 Summer Olympic Games held in Antwerp, Belgium. The final saw Canada defeat Sweden 12-1 to claim the first ever Olympic gold medal in ice hockey. The team's leading scorer was Frank Fredrickson, who notched 12 of the Falcons' 29 goals in the tournament.

8. 1924 Winter Olympics (Toronto Granites)

A group of talented amateurs from Toronto took home the first Olympic Gold in ice hockey at a Winter Olympics. At the 1924 Chamonix Olympics, the Granites tore through the competition with devastating efficiency, scoring in bunches and allowing only 3 goals in 5 games. The opposition didn't stand a chance. Harry Watson was the undoubted star of the final which saw Canada defeat the United States 6-1. "After the game the Americans declared Watson the greatest hockeyist of all time," The Star wrote. "They said no other player ever took so much punishment and played such brilliant hockey."

9. 1928 Olympics (University of Toronto Graduates Hockey Team)

Canada was represented in ice hockey by the University of Toronto Grads. It was a formidable team, having won the Allan Cup and being coached in Canada (though not at the Olympics) by Conn Smythe. Given the strength of the Canadian team, the tournament organizers advanced Canada directly to the final round, where the Grads steamrolled the Swedes 11–0, Great Britain 14–0 and the host Switzerland 13–0. After their gold medal performance, the team toured Europe, introducing large crowds to their speedy play. At 21 years old, Canadian Dave Trottier, was the most sought after player in the world and he had yet to turn pro. Trottier scored five goals in each of the first and the final games of the tournament, managing a meagre pair against the British, and with those 12 goals he shared the tournament’s scoring lead with teammate Hugh Plaxton.

10. 1932 Olympics (The Winnipeg Hockey Club or Winnipegs or Winnipeggers)

Led by their leading scorer (5 goals in 6 games), Romeo Rivers, The Winnipeg Hockey Club won Canada’s fourth consecutive Olympic medal in ice hockey at the 1932 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, United States.

11. 1948 Olympics (RCAF Flyers)

The RCAF Flyers represented Canada at the Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland in 1948, and against all odds, came home with a gold medal. Why was it such an extraordinary achievement? Well, Canada’s 1948 Olympic hockey team was not comprised of the top league players as would normally be the case. In fact, it was made up of military and ex-military men, hurriedly pulled together under the banner of the RCAF, to represent the country’s best hockey talent. Even before the team sailed for Europe in January 1948, fans and skeptics in the press had written them off as “a less than encouraging sight.”

A decision by the IOC {International Olympic Committee) during the latter part of 1947 affected the status of amateur athletes and their eligibility to participate in the games. The new rules made it impossible for the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) to assemble a team good enough to compete and still meet the new IOC regulations. With this in mind it was decided that for the 1948 Winter Olympics there would be no Canadian national hockey team participating at the event. The news was greeted with astonishment. The top officials in the air force, the Ministry of Defence and the CAHA were lobbied, suggesting the RCAF, with its 16,000 members, would be the best resource from which to draw the most talented amateur athletes. With a scant three months to go before the games were to start, the search for a team began. More than 75 air force hopefuls were flown to Ottawa for tryouts from bases all over the country. A series of exhibition games were organized during December to bring the final 17 players together but the results were less than impressive, losing 7-0 in their first game against a team from McGill University. However, with an additional run of exhibition games scheduled for Europe, in the weeks leading up to the event, the team was confident it would improve.

The Winter Olympics opened on January 30th, 1948 with the Flyers beating Sweden 3-1 in their first game on an outdoor rink. Despite the problematic winter weather, games went ahead even in blowing snow as was the case when the Flyers beat the British team 3-0 in near whiteout conditions. Dodging snowballs thrown by an irritated Swiss crowd which disagreed with the officiating, and the slushy ice cut up by the figure skaters, was all part of the extraordinary circumstances that met the Canadians in St. Moritz.

After beating Poland 15-0, the United States 12-3, Italy 21-1, Austria 12-0 and Switzerland 3-0, the Flyers were tied with the Czechs, both teams holding 7 wins, 0 losses and 1 ti . In calculating the goals for and goals against average, the decision fell to the Canadians, which in large part was a result of their outstanding goal tending … and the gold was awarded to Canada.

It had been a remarkable event that has since become part of Canadian hockey history. The RCAF Memorial Muse um display is a fitting acknowledgment of the tenacity and sheer resol\’e of the Canadian players who were expected to be quickly eliminated by the stronger European teams, players who were serving their country in more ways than one.

Today, the 1948 RCAF Flyers World Champions banner hangs over the ice at the new rink named in their honour at Canadian Forces Base in Trenton. (credit author: Frank Artes)

12. 1952 Edmonton Mercurys

The Mercurys represented Canada at the 1952 Olympic Games in Oslo and won gold. This would be Canada’s last Olympic gold in Olympic men’s hockey for 50 years! It wasn't until 2002, that Canada (led by Joe Sakic, Mario Lemieux, Martin Brodeur and Co.) would win again.

The Mercurys were chosen in 1952 because they were deemed to be 100 percent amateur. All their members were employees of the Waterloo Mercurys car dealership in Edmonton. A number of other amateur teams applied for the right to represent Canada, but it was too cost prohibitive to have a national tournament to determine a representative. And because the Mercurys won the World Championship title in 1950, it was decided they would represent the country well.

At Oslo 1952, Billy Dawe was captain of the Canadian hockey team mostly made up of players from the Edmonton Mercurys team. In the round-robin tournament, Canada and the United States tied 3-3, but Canada did not lose a game and won the gold medal, as the Americans had lost to Sweden, 4-2. Dawe played in eight games and scored six goals. Heralded on the ice for his slick skating, Dawe was also a member of Mercurys that represented Canada at the 1950 World Championships where he won a gold medal.

13. 1984 Canada Cup

Canada was a disappointing 2–2–1 in the round-robin of the 1984 Labatt Canada Cup. There was inner turmoil on the roster, which was dominated by players of two NHL powerhouses, the Edmonton Oilers and the New York Islanders—these two teams had faced off in the past two Stanley Cup Finals, and there were bitter feuds between players that had to be overcome. In the semi-final, versus a perfect 5-0 USSR team, Canada dominated the first two periods, but managed only a 1–0 lead due to spectacular goaltending from Vladimir Myshkin. The Soviets scored twice in the third to take the lead, but defenceman Doug Wilson tied the game late in regulation. In overtime, Myshkin continued his brilliant play. The Soviets got a two-on one against the flow of the play, but were thwarted by a brilliant poke-check by Paul Coffey, who was normally an offensive defenceman. Later on that play, Coffey's point shot was deflected in front of the net by Mike Bossy for the winning goal. In the other semi-final, Sweden upset the USA 9-2 despite having lost to them 7-1 in the round robin. Canada swept the best of three final and Canadian forward, John Tonelli, was named the tournament's most valuable player.

14. 1990 World Women's Championship

The 1990 IIHF Women's World Championships was an international women's ice hockey competition held at Civic Centre in Ottawa, Ontario (now renamed TD Place Arena). This was the first IIHF-sanctioned international tournament in women's ice hockey and was the only major international tournament in women's ice hockey to allow bodychecking. The tournament drew strong international attention. The gold medal game packed 9,000 people into the arena and drew over a million viewers on television. For marketing purposes, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association decided the Canadian national team should wear pink and white uniforms instead of the expected red and white and released a related film called, "Pretty in Pink". While the experiment only lasted for this tournament, Ottawa was taken over by a "pink craze" during the championships. Restaurants had pink-coloured food on special, and pink became a popular colour for flowers and bow ties.

In her first year at the University of Manitoba, Susana Yuen was encouraged by a former teammate to join the university’s women’s hockey team. The 4'10" Yuen showed up for the first practice with garbage mitts and sweatpants. Looking around at the other players with their full sets of equipment she quickly realized this was a whole new game she was getting into. Playing with the Lady Bisons in 1984 was Yuen’s first competitive hockey experience.

Four years later, recruiters for Team Canada got in touch with the league. They were looking to build a roster for the inaugural world championship and three players from Manitoba had a chance to skate at the selection camp. Yuen put her name forward and received a call saying she was welcome to play, for a cost of $50. “I didn’t have any expectations of making a national team,” she said. “When I went, I was in awe of everything, and in awe of seeing the skill level of the players there.”

The world championship was a stepping stone for women’s hockey and the progression of the game in Canada, Yuen said, and made it acceptable for young female athletes to play hockey. Susana made the team and her 5 goals and 7 assists at the 1990 WWC put her in the tournament's top 10 scorers. Her 6 point single game performance remained a National team record until 2007.

The event would be a watershed moment in the women's game. The abilities of elite female players from around the world were showcased earning support to include women's ice hockey in the 1998 Olympic Games. Yuen's gritty performance in the tournament is understated in the impact it had on the women's game

15. 1991 Canada Cup

The 1991 Labatt Canada Cup finals took place in Montreal, and were won by Canada. The Canadians defeated the USA in a two-game sweep, to win the fifth and final Canada Cup. The tournament was replaced by the World Cup of Hockey in 1996. Of the five Canada Cup tournaments, this is the only one in which a team went undefeated; Canada compiled a record of six wins and two ties in eight games. This wasn't surprising given the strength of the Canadian roster. They were missing some big names, with Mario Lemieux out with a back injury, Steve Yzerman cut by Mike Keenan, and Joe Sakic, Patrick Roy, Ray Bourque and Cam Neely also absent. But the roster was still stacked, featuring in-their-prime stars like Wayne Gretzky, Mark Messier and Scott Stevens.

By the time the final matchup between Canada and the U.S. had been set, the storyline seemed clear. You had the dominant favorite taking on the scrappy underdog, in a battle that pitted a modern hockey powerhouse against what many viewed as its inevitable replacement.

But that story was quickly overshadowed after a controversial moment in the opening game. Team USA defenseman Gary Suter plastered Gretzky into the end boards on an unpenalized hit from behind that knocked the Canadian star out of the tournament. The hit left Team Canada furious, and made Suter the country's most-hated villain (a role he reclaimed years later when he knocked Paul Kariya out of the 1998 Olympics).

Ultimately, Gretzky's absence didn't slow Canada down. It won the opening game 4-1, then took the second game by a 4-2. Gretzky finished as the tournament's leading scorer, and goaltender Bill Ranford was named tournament MVP.

16. 2004 World Cup of Hockey

Canada finished the 2004 World Cup of Hockey with a perfect record of 6-0-0. With this victory, Canada had won four of the last five major senior men’s international hockey tournaments since 2002, and held a record of 30-4-3 during that time (gold - 2002 Winter Olympics, gold- 2003 World Championship, gold - 2004 World Championship, 1st - World Cup of Hockey 2004). Vincent Lecavalier was named player of the tournament. Shane Doan had the game winner in the final for Canada versus Finland.

19. 2006 Olympics (Women)

Cassie Campbell was the captain of the Canadian women's ice hockey team during the 2002 Winter Olympics and led the team to a gold medal. The left winger took on the role of captain again in the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy, and again successfully led her team to a gold medal with a 4–1 win over Sweden. She is the only Canadian hockey player, male or female, to captain teams to two Olympic gold medals; a feat she accomplished after taking the "C" in 2001 and wearing it until she retired five years later.

20. 2007 Spengler Cup

The 2007 Spengler Cup was held in Davos, Switzerland. The final was won 2-1 by Team Canada over Salavat Yulaev Ufa.

Ryan Smyth, often referred to as “Captain Canada”, represented Canada twice at the Olympic Games and eight times at the IIHF World Championships. In total, he appeared in 89 international games, scoring 21 goals and 19 assists.

Smyth’s Olympic debut was at Salt Lake City 2002 where he and Team Canada captured gold to end a 50-year Olympic title drought in men’s hockey. Smyth also competed at Turin 2006 where he appeared in six games for Canada.

Smyth first wore the maple leaf at the 1995 IIHF World Junior Championship where he recorded seven points (two goals, five assists) in as many games, enroute to Canada winning the gold medal. In his eight IIHF World Championships, Smyth served as captain five times and set the record for the most IIHF World Championship games played by a Canadian with 60. He won gold with Team Canada in 2003 and 2004 to go with a silver in 2005.

Smyth also played in the 2004 World Cup of Hockey and helped Canada take home gold. Smyth was named to the Order of Hockey in Canada in 2018.

Smyth was inducted to the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame in 2009 with his teammates from the 2002 Olympic hockey team.

21. 2014 Olympics

This win gave Canada its second consecutive Olympic gold, the first time it had stood atop the podium at back-to-back Games since 1948 and 1952. The Canadians are also the first to successfully defend their gold medal since the Soviet Union in 1988. Jonathan Toews scored the game winner as Canada defeated Sweden 3-0. It was the second straight Olympic gold medal game that Toews had opened the scoring; he broke the ice at 12:50 of the first period against the United States in 2010. Canada set a modern Olympic record for fewest goals allowed in an Olympic men’s hockey tournament; it gave up just three in six games. Drew Doughty was the lone Canadian to earn a spot on the media all-star team; he finished as Canada’s leading scorer, with four goals and two assists in six games.

22. 2015 World Juniors

Connor McDavid represented Canada at several international competitions prior to his NHL career. He won gold medals at the 2013 IIHF World U18 Championships and 2015 World Junior Championships.

23. 2016 World Cup of Hockey

After a 12 year hiatus, the World Cup of Hockey returned in 2012. Brad Marchand scored shorthanded with 44 seconds left in the third period and Canada defeated Team Europe 2-1 to win the 2016 World Cup of Hockey. Canada swept the best-of-three final series. Marchand took a drop pass from Jonathan Toews and fired a shot from between the hash marks, beating Jaroslav Halak and putting an exclamation point on a fantastic tournament. The forward finished with eight points, including a team-leading five goals. Sidney Crosby, was named the Most Valuable Player. Marchand, Crosby and Bergeron were the team’s – and the tournament’s – best line, combining for 25 points in the tournament.

Canada had been the dominant team the entire tournament. Coming in the team had won 15 straight games in best-on-best competition: it was a perfect 5-0 at the World Cup, 6-0 at the 2014 Olympic Winter Games and had won its last four at the 2010 Games. In 2016 they outscored their opponents 22-7, outshot them in 12 of 15 periods and successfully killed off all 15 penalties called against them.

For 57 minutes on Thursday night none of that mattered. Zdeno Chara gave Team Europe the lead 6:26 into the first period. Chara, booed every time he touched the puck both tonight and in Game 1 on Tuesday, took a short pass from Andrej Sekera and beat Price from the middle of the left face-off circle. For the longest time it looked like it would be enough to force a winner-take-all game on Saturday. Team Europe outshot Canada in both the first and second periods, and its ability to neutralize the Canadian attack had the underdogs thinking upset. But mixing up its lines to start the third period seemed to give Canada the jolt it needed. With the win Canada has now won six of the eight World and Canada Cups contested.

24. The Lucky Loonie

Prior to the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, Trent Evans and his team of icemakers from Edmonton, Alberta were contracted to lay down the playing surface for the men’s and women’s hockey tournaments. After arriving in Utah, Evans began building the playing surface at the E Center in West Valley City, which would host most of the hockey action, including the medal games. Needing to identify the area at center ice where the officials could drop the puck for face-offs, Evans placed a Canadian dime he had in his pocket to mark the center of the rink. After laying down the first layer, he covered the dime with a loonie. More layers of ice were added, along with the Olympic snowflake logo and a small orange dot, marking center ice. Evans, however, choose not to remove the Canadian coin, imagining that it would serve as a piece of good luck for his native teams as they played in Salt Lake City, away from home.

As the players, coaches, and team staff arrived, including hockey’s most legendary figure, Wayne Gretzky, who was serving as the team’s executive director, Evans would whisper that he left a piece of Canada in the ice at the tournament’s marquee arena. Remembering a passing encounter with Gretzky in which he mentioned his sneaky deed, Evans recalled The Great One telling him to keep it quiet, and that the word had already reached him.

“He said ‘Yeah I know about it,’ there were enough people around that it wasn’t a loud conversation, but it was like just ‘zip it, Trent, let’s keep this secret,’” Evans recalls.

As the tournament progressed for both the women’s and men’s teams, the rumor of a loonie under center ice at the E Center spread throughout the Canadian hockey inner circles. Afraid that the story of the lucky loonie would leak out to the media or the host country’s Olympic committee, the secret was closely guarded. It became extremely important to Gretzky that the loonie remain in the ice as the Canadians advanced through the tournament.

The ploy was nearly ruined, however, after the women’s gold medal game when a few members of Team Canada began kissing center ice in celebration of their 3-2 victory over the United States. It was a stressful moment for both Gretzky and Evans.

“I was like ‘Get them away from the loonie because we want this to last to the men’s gold medal game as well,’” Evans recalls. “I didn’t know this at the time, but Gretzky was also on the phone, freaking out, telling them to get the girls away from center ice.”

Luckily, the loonie remained embedded in the ice three days later when the men played the United States for the top prize. Like the women before, the Canadian men prevailed over the U.S. to capture the title, the hockey-crazy country’s first men’s Olympic hockey gold since 1952. As the players swarmed the ice to celebrate their 5-2 victory over the Americans, Evans prepared to extract the now priceless loonie from the ice. After the squad took a team picture at center ice, with their gold medals wrapped around their necks and the lucky coin just inches below them, Evans and another crewmember rushed onto the surface to free it from its frozen clutches.

Using a cup of hot water and a screwdriver, Evans retrieved the coin and handed it to Kevin Lowe, a longtime hockey executive and former player who was serving as an assistant to Gretzky during the Games. As the two walked towards the Canadian locker room where Gretzky and the players were basking in the moment, Lowe turned to the icemaker and insisted that Evans be the one to hand the coin to Gretzky. To Evans, that gesture was the highlight of his soon-to-be-legendary Olympic moment.

“He didn’t want it, he didn’t want to take the limelight of the loonie, so he gave it to me,” Evans says of Lowe’s insistence.

With the loonie, along with the original dime clanging around in his pocket, Evans continued to make his way towards Gretzky. As he moved through the bowels of the arena, he overheard some media members talking about a rumor circulating that the Canadians had planted a coin at center ice. Evans remembers giggling to himself as he heard the chatter, knowing he had the rumored loonie in his pocket.

After finishing a lap around the inside of the arena, Evans arrived outside the temporary locker room which was built for Team Canada. There, he presented the good luck charm to Gretzky and team captain Mario Lemieux. Smiling and soaking in the triumph of Canada’s first Olympic hockey gold medal in 50 years, Gretzky held the coin in the air and declared, “We’re going to put that in the Hockey Hall of Fame.”

Describing Evans’s work to put the coin in the ice to inquiring reporters and cameramen, Gretzky joked, “A little bit of luck, having a little bit of Canada in the ice." True to Gretzky’s word, the loonie was sent to the Hockey Hall of Fame and given a special display case ahead of Canada’s turn to host the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, where the men’s hockey team also won the gold medal.

25. Don Cherry

As a co-host on Hockey Night in Canada, and a huge supporter of the Canadian game, Don Cherry was a fixture, alongside Ron MacLean, on Team Canada game broadcasts. In 2004, Don Cherry was voted by viewers as the seventh-greatest Canadian of all-time in the CBC miniseries The Greatest Canadian. Cherry remarked that he was "a good Canadian", but not the greatest Canadian.

On November 14, 2005, Cherry was granted honorary membership of the Police Association of Ontario. Once an aspiring police officer, Cherry has been a longtime supporter of the police services. In his own words, "This is the best thing I've ever had." In June 2007, Cherry was made a Dominion Command Honorary Life Member of the Royal Canadian Legion in recognition of "his longstanding and unswerving support of Canadians in uniform". In February 2008, Cherry was awarded the Canadian Forces Medallion for Distinguished Service for 'unwavering support to men and women of the Canadian Forces, honouring fallen soldiers on his CBC broadcast during Coach's Corner, a segment of Hockey Night in Canada'. In 2016, Cherry, along with his Coach's Corner co-host Ron MacLean, received a star on Canada's Walk of Fame.

Cherry was an assistant coach for Team Canada at the 1976 Canada Cup and was head coach for Canada's team at the 1981 World Championships in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Cherry is a staunch supporter of women's hockey, and sledge hockey. In 1997, the Canadian women's national ice hockey team paid tribute to the late Rose Cherry. Canadian Hockey chairman Bob MacKinnon thanked Cherry stating "The growing popularity of the women's game in our country owes a great deal to Don and Rose Cherry... Don has been a strong supporter of the female game since the early 1980s and continues to speak out in favour of women's hockey. It's a pleasure for me, as chairman of Canadian Hockey, to be a part of this tribute to Rose Cherry, who was a keen supporter of female hockey herself."

Customer Reviews

Based on 3 reviews

Write a review